By Benjamin GroffMedia© | benandsteve.com | 2025 Truth Endures©

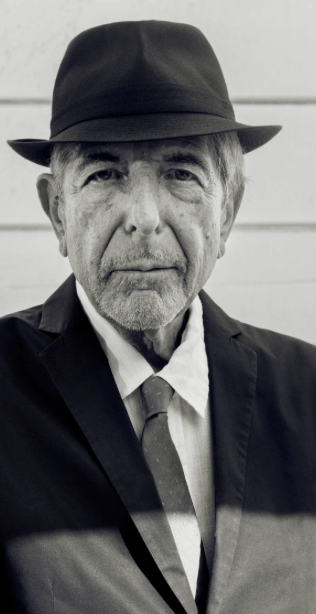

The True Meaning of Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah

Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah has become one of the most widely recognized and performed songs in modern music history. It’s played at weddings, funerals, church services, and talent shows. But in all the repetition and repurposing, something essential has been lost.

Cohen never intended Hallelujah to be simply beautiful. He intended it to be raw. Complex. Human.

The song is not a hymn of praise in the traditional sense. Instead, it’s a poem set to music, a confession wrapped in biblical language and erotic undertones. It’s about a man watching a woman undress from a rooftop. He watches not in an act of love, but of longing and helpless craving. He stands in his kitchen, overwhelmed and isolated. The “hallelujah” he utters is not holy—at least not in the religious sense. It is a broken hallelujah. It is born from the ache of wanting and not having. It is the result of touching something divine through deeply human hunger.

Cohen interweaves the sacred and the sensual because, for him, they were never far apart. Verses reference King David, Bathsheba, Samson and Delilah—figures whose passions brought them into both ecstatic heights and tragic ruin. Cohen wanted to explore this contradiction. He wanted to understand how love, lust, faith, betrayal, and surrender all live side by side in the human soul.

“There’s a blaze of light in every word. It doesn’t matter which you heard. It could be the holy or the broken hallelujah.”

The tension in Hallelujah is not just between sacred and profane, but between understanding and mystery. Why do we feel what we feel? Why do we cry out “hallelujah” even when we are lost or ashamed?

Later in life, Cohen was said to feel some regret. He was unhappy over how the song had been turned into a feel-good anthem. It was stripped of its edge and stripped of its truth. Many of the popular covers—Jeff Buckley’s, John Cale’s, even k.d. lang’s—choose only a few of the verses, removing the darker or more explicitly sexual lines. What’s left is haunting, but incomplete.

Cohen reportedly wrote over 80 verses for Hallelujah. The versions we know today are fragments—reflections of reflections. But they carry within them that strange, shimmering truth: that pain and praise can live in the same breath.

In one interview, Cohen said:

“This world is full of conflicts and full of things that can’t be reconciled. But there are moments when we can… and the song ‘Hallelujah’ is about those moments.”

Those moments—the mingling of joy and sorrow, flesh and spirit, light and shadow—are what make Hallelujah more than a song. They make it a mirror.

We don’t all shout our hallelujahs from rooftops. Some of us whisper them from the corners of our kitchens, alone, longing, and unsure. But that doesn’t make them any less true.

That’s the Hallelujah Leonard Cohen wrote.