Lessons in Trust from Mom and Pop’s Living Room

By Benjamin GroffMedia© | benandsteve.com | ©2026

I was five or six years old in 1968. That is the thought I had at midnight when I couldn’t fall asleep. I tried counting sheep to fall asleep. Nevertheless, every time one got over the fence, I thought of the Pink Panther cartoon. There was an episode where that cool pink cat finally got all the sheep counted onto one side. Then, they stampeded back and trampled him in bed. I worried that happen to me. So I paused.

By then, I’d lost my place anyway. Was I on thirty-five? Or forty-five? I laughed quietly to myself and started thinking about where I first saw that Pink Panther episode. Ah, yes—the living room floor at my grandparents’ house. I had to have been five or six.

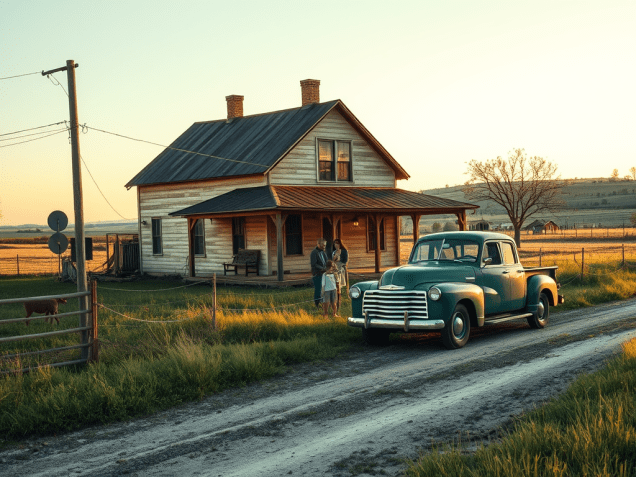

That memory sent me down an entirely different path. I started thinking about my grandparents—Mom and Pop, as I always called them in my stories. Mom was in her seventies, Pop in his eighties. Their home was my escape on many weekends and long summer days. Life there felt simple, steady, and safe.

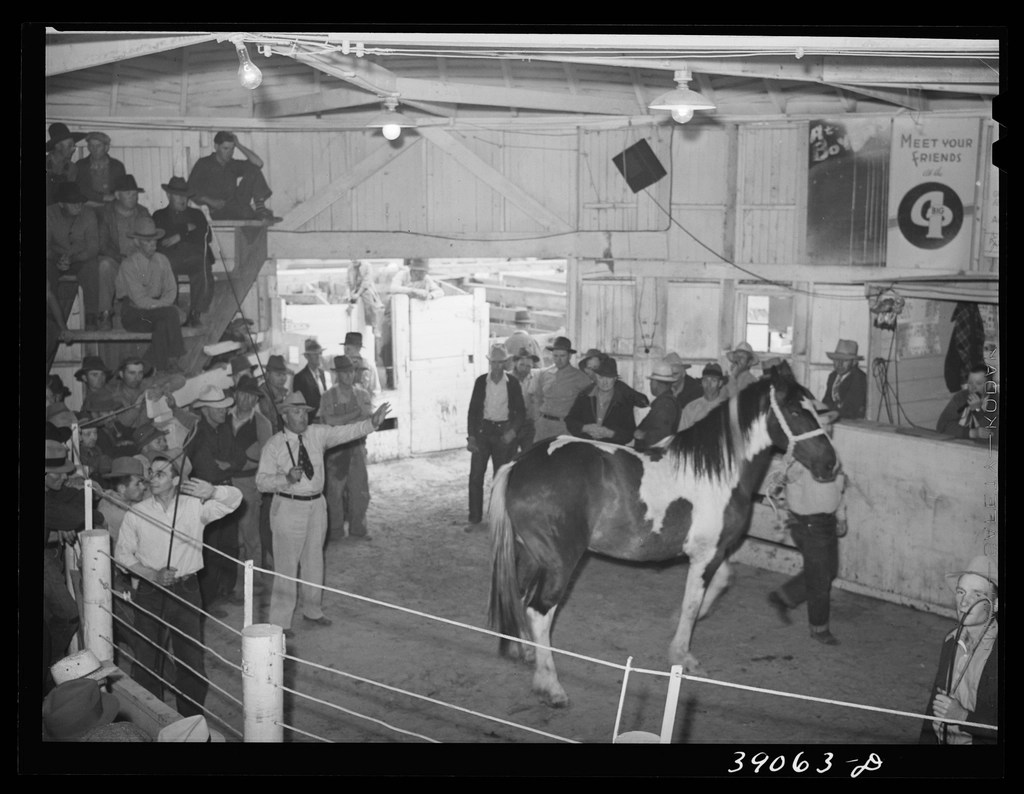

Mom kept a half-gallon tin can filled with treasures. It contained an old set of dominoes, tiny farm animals, and a little truck. I imagined it hauled just about anything. On the linoleum floor of their den, I spent hours building domino fences to keep the animals contained. Sometimes I hauled them off to market. Other times, I stacked the dominoes carefully into what I imagined was an oil derrick. In 1968, an imagination was powerful. An incomplete set of dominoes became anything a kid wanted it to be.

While I worked, Mom rocked gently in her chair, watching me with a smile as her bird, Billy, sang nearby. Pop sat with his pipe, sending out a steady stream of smoke from his Prince Albert tobacco. That bucket of toys kept me busy all day—or so it seemed. I never thought about the world changing beyond that setting.

If I ever got tired of farming, there was something else waiting in that tin can: a long cotton rope. It was also there if I got tired of building oil wells. And the rope was always for one thing—getting hogtied.

The rules were simple. I had to lie still. No kicking. Pop would tie my hands and feet together behind my back. Then wait until the clock on the china cabinet struck the top of the hour. Only then I tried to get loose. I couldn’t kick myself free—I had to work the knots with my hands. It usually took a good hour, but I always managed to escape.

It wasn’t unusual for neighbors to stop by while the grandson was hogtied on the floor. Jimmy Schriver, who lived across the street and stopped in nearly every day, sometimes offered advice. He even tried to help once or twice, which earned him a sharp rebuke from both Mom and Pop.

“No,”

They’d say.

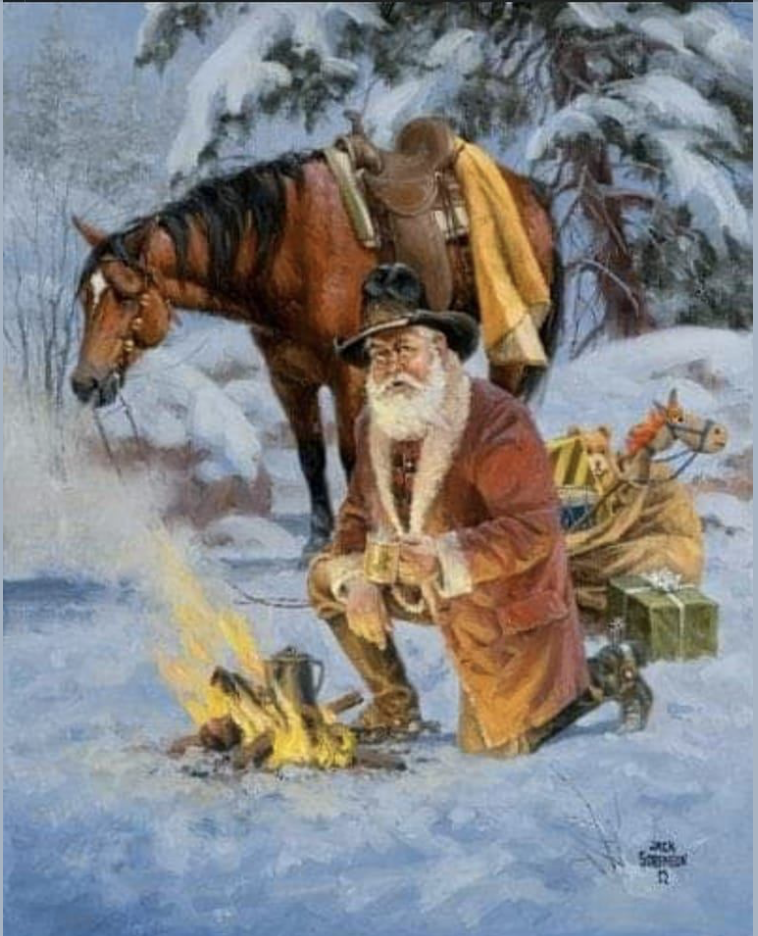

“He must learn to escape from being hogtied. It’s crucial in case his horse gets stolen. And he gets tied up on the trail.”

To a five-year-old, that sounded perfectly reasonable. My dad and I rode horses often. I watched plenty of Roy Rogers, Dale Evans, Rawhide, and Gunsmoke. This showed me that such things happen. In reality, I’ve never been hogtied by anyone other than my grandparents—but back then, it felt like practical training.

Lying awake that night, I decided not to count sheep or cattle anymore—no sense risking a stampede. Instead, I wondered how my grandparents would be viewed today. What would someone think if they walked in and saw a child tied up on the floor? The child would be working knots while waiting for the clock to chime.

The more I thought about it, the smarter those two old-timers seemed. They discovered how to channel the boundless energy of a child. They couldn’t outrun or outplay the child. Instead, they turned that energy into patience, problem-solving, and imagination.

We played other games—wahoo, dominoes, bingo—but hogtying is the one that stayed with me. I’d look ridiculous asking for it now. If I see Mom and Pop again someday, I’d know which game to play first.

What I understand now is far more clear to me than it ever was back then. They were not really teaching me how to escape a knot. They were teaching me trust. Trust that I was safe. Trust that I could struggle and still be watched over. Trust that someone would always be nearby. They let me work it out on my own. They never let harm come to me. Being hogtied on that linoleum floor wasn’t about restraint. It was about freedom within boundaries. It was about confidence built quietly. It was the unspoken assurance that I was loved enough to be protected while learning how to untangle myself. That kind of trust, once given, stays with you for life. And today, would probably cause you to lose custody of your children.

By Benjamin GroffMedia© | benandsteve.com | ©2026