By Benjamin GroffMedia© | benandsteve.com | 2025 Truth Endures

A Frightening, Comical, and Hostile Ride: The Birth of Twila Elouise

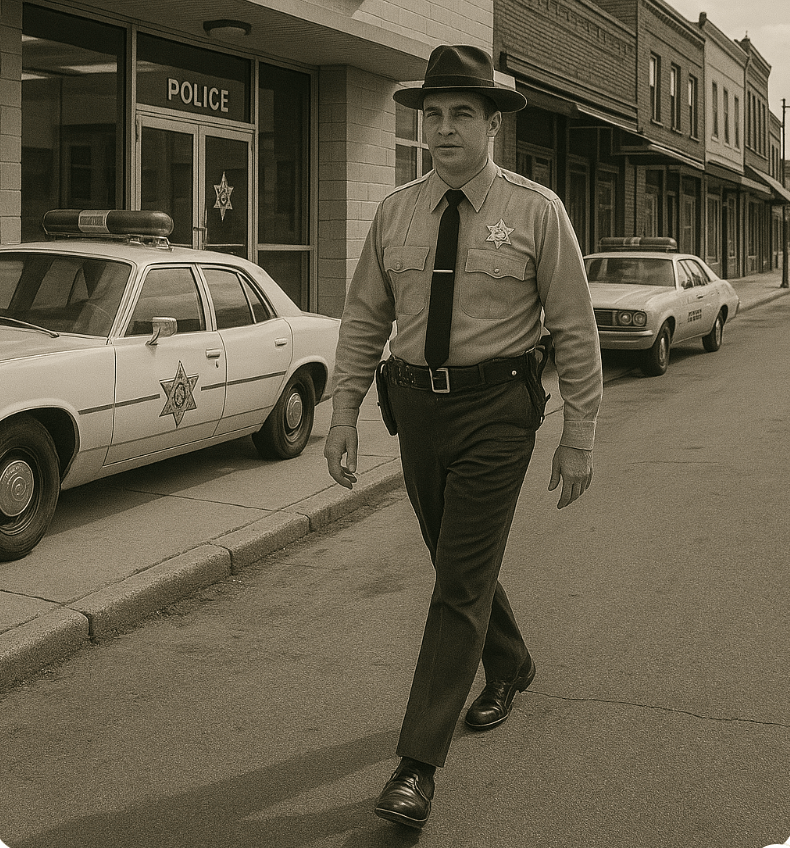

By early June of 1960, Oklahoma’s summer heat had already settled in, pressing down across the vast plains. In Oklahoma City, JD Groff attended a convention of oil producers. He was representing Standard Oil Company alongside his superior. His superior was a man named Harold. Harold had a reputation for being both respected and heavy-handed with a whiskey glass.

Meanwhile, back in Clinton, JD’s wife Marjorie—known to family and friends as Margie—had decided to stay home during JD’s trip. Margie had four children already—Sheldon, Terry, Dennis, and Juli. She wanted to stay close to JD’s sister and brother-in-law. They could quickly step in and help with the kids if she needed to go to the hospital. It was a decision made with foresight and care, and as it turned out, it was the right one.

On June 2, Margie went into labor.

Her calm steadiness defined her actions. She went to the hospital, and the children were safely in good hands. Virgil Downing, her son-in-law, knew that JD needed to be reached quickly. He called the hotel in Oklahoma City. The oil convention was being held there. He had the front desk page, JD Groff.

“They called my name right in the middle of the banquet,”

JD later recalled.

“Everything stopped. I knew right then — it was time.”

JD bolted from the room, his heart pounding and his hands reaching for his keys when Harold intercepted him.

“You’re not driving,”

Harold slurred, wagging a finger.

“You’ll crash the damn car. You’re too excited, Groff. I’ll take you.”

JD tried to argue and pry the keys back, insisting that Harold should not drive. He even asked him multiple times to pull over. They should then switch places. Harold refused every time. He repeated with drunken certainty that he was the safer choice.

“You’ll wrap us around a tree,”

Harold barked, gripping the wheel with one hand and gesturing wildly with the other.

“You’re gonna be a daddy tonight, shaking too much to steer.”

A two-hour rollercoaster ride across the Oklahoma highways followed. It was a journey that JD would remember for the rest of his life.

“He passed cars on the left, passed them on the right,”

JD said later.

“He cussed at every truck, hollered at every red light, and nearly rear-ended a tractor. At one point, he tried lighting a cigar while doing 80 down a back road.”

As JD would describe,

“frightening, comical, and hostile all at once.”

By some miracle, they made it to Clinton in one piece. JD leaped from the car, bolted into the hospital, and made it to Margie’s side just in time.

That evening, on June 2, 1960, their daughter was born: Twila Elouise Groff.

JD had already picked the name. Twila for its soft, lyrical sound. Elouise served as a tribute to the Groff family lineage. This name stretched back to the family’s Swiss heritage. It was carried by strong women long before the Groffs ever set foot in America.

Twila’s birth quickly became more than a family milestone — it became a local legend.

In the next weeks and months, oil producers stopped by JD’s Standard Oil station in Clinton. Sales associates also visited. Colleagues from the convention came by as well. They checked in.

“How’s the baby?”

They’d ask.

“Did Harold drive you the whole way like a bat out of hell?”

Before long, the story had taken on a life of its own. Twila became affectionately known among oil company executives as

“The Standard Oil Baby.”

Her name would be mentioned at future conventions and meetings across Oklahoma. JD’s wild ride—and Twila’s prompt arrival—became an industry folklore, retold with laughter, awe, and camaraderie.

Years later, when new sales associates came through Clinton, they’d stop in and say,

“Is this where the Standard Oil Baby lives?”

And JD, with that familiar half-smile, would nod proudly and say,

“Yes, sir. That’s her.”