By Benjamin GroffMedia© | benandsteve.com | ©2026

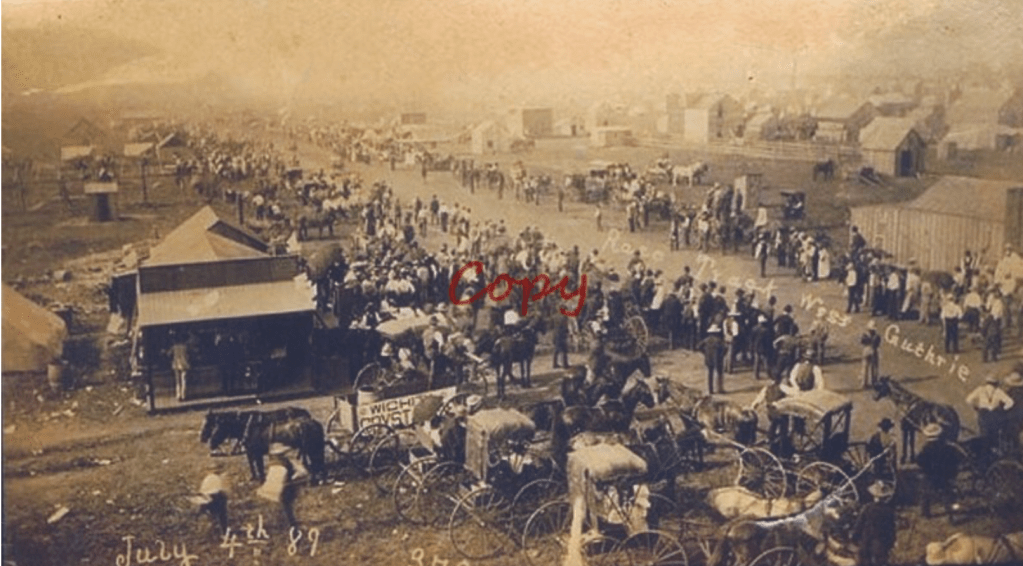

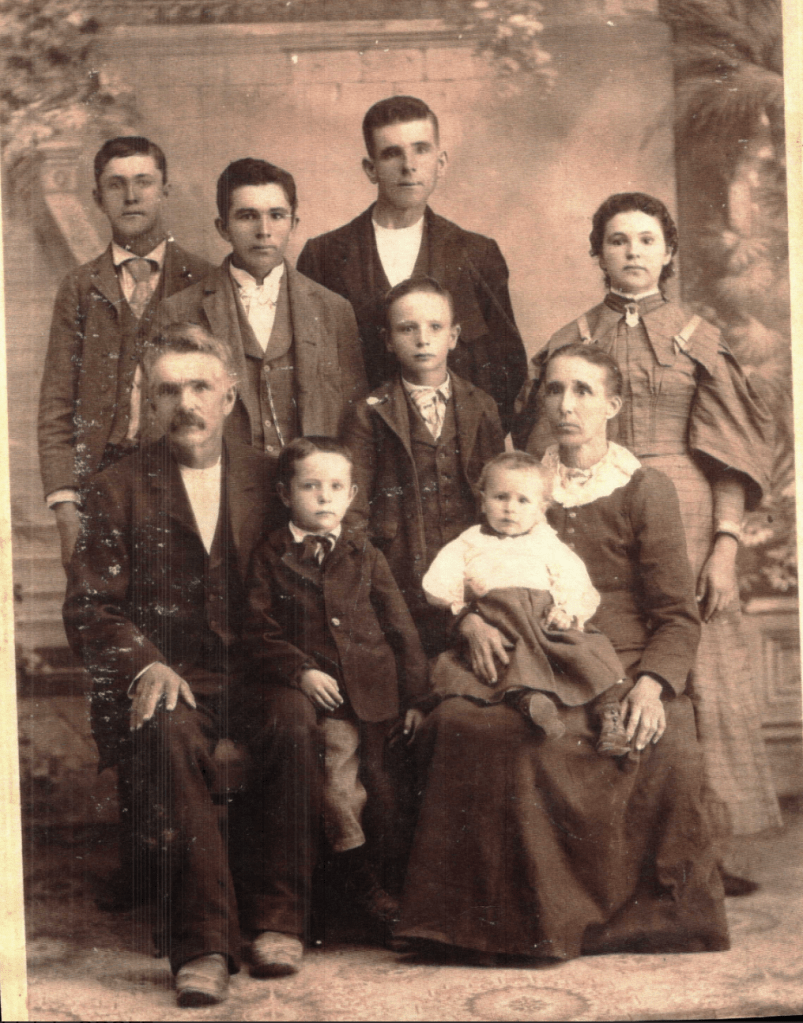

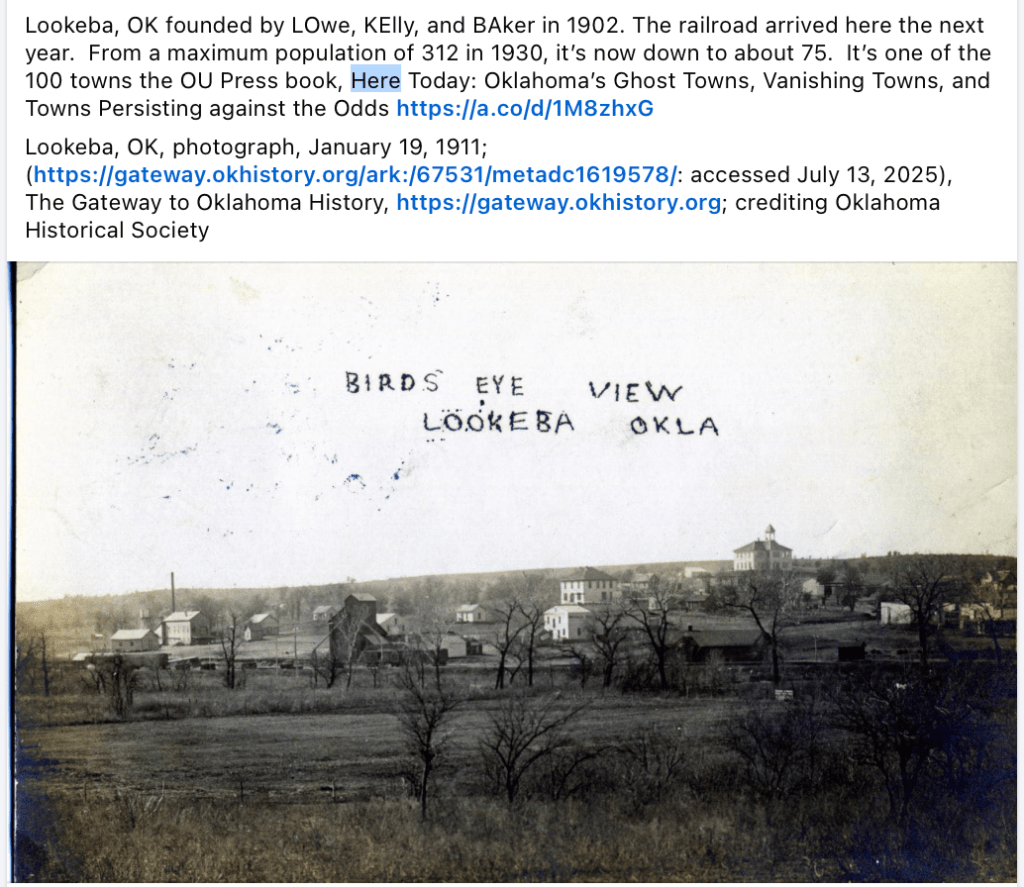

Most folks drive along the stretch of Oklahoma highway between Binger and Anadarko. They roll past Lookeba without ever knowing they’ve entered a place. This place is built on three simple names—Lowe, Kelly, and Baker. These names are stitched together like a handshake. Lookeba. A name that sounds almost tribal or mythic. Yet it originated from the ordinary people. They did what settlers always did in early-day Oklahoma: carved a life out of red soil and hope.

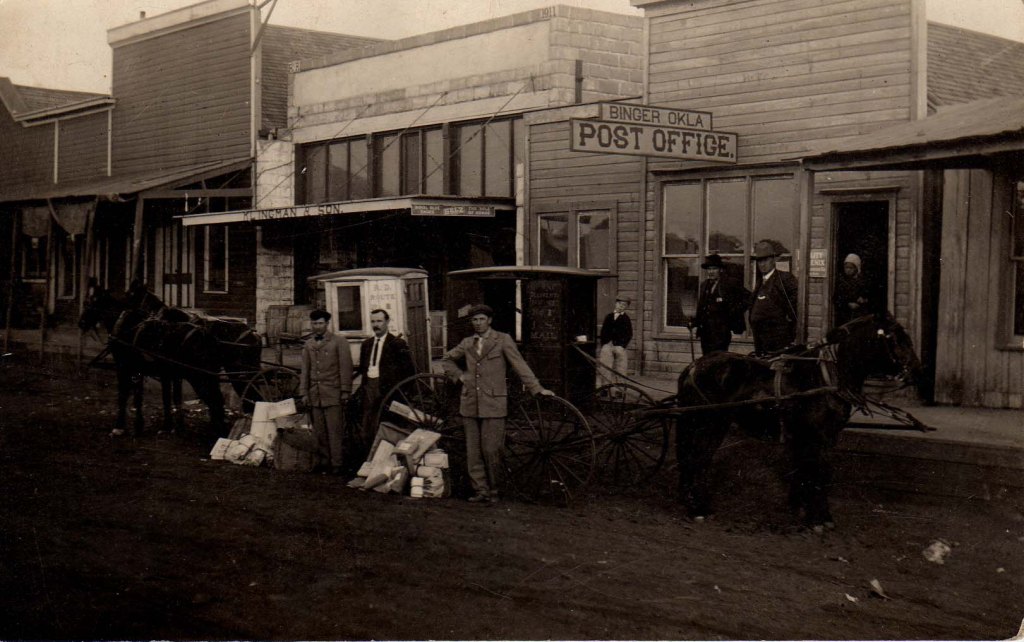

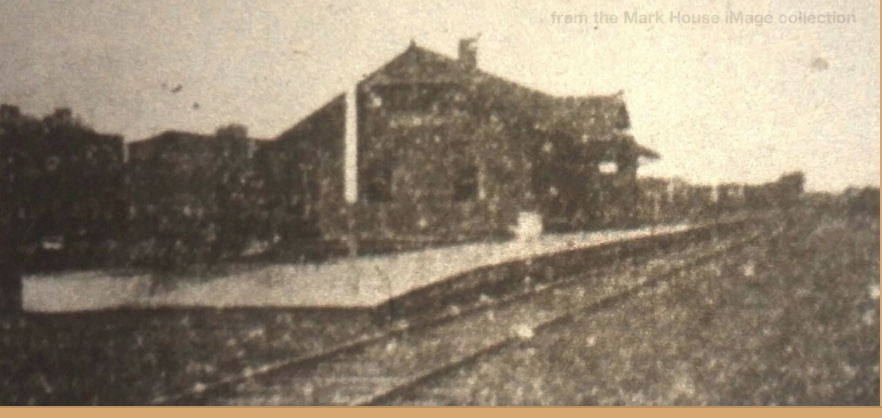

Lookeba began as a crossroads community. It was a depot stop on the journey between larger towns. It was a place where wagons once creaked through cottonwood shade. Dust settled on the porch rails of the general store. Early schoolhouses rattled with the laughter of children carrying family names that would define the region for generations. The town’s claim to fame wasn’t oil or railroads or long sweeping history—it was quiet endurance. The land rolled gently. Storms gathered thick on the horizon. People stayed because they felt stitched to it.

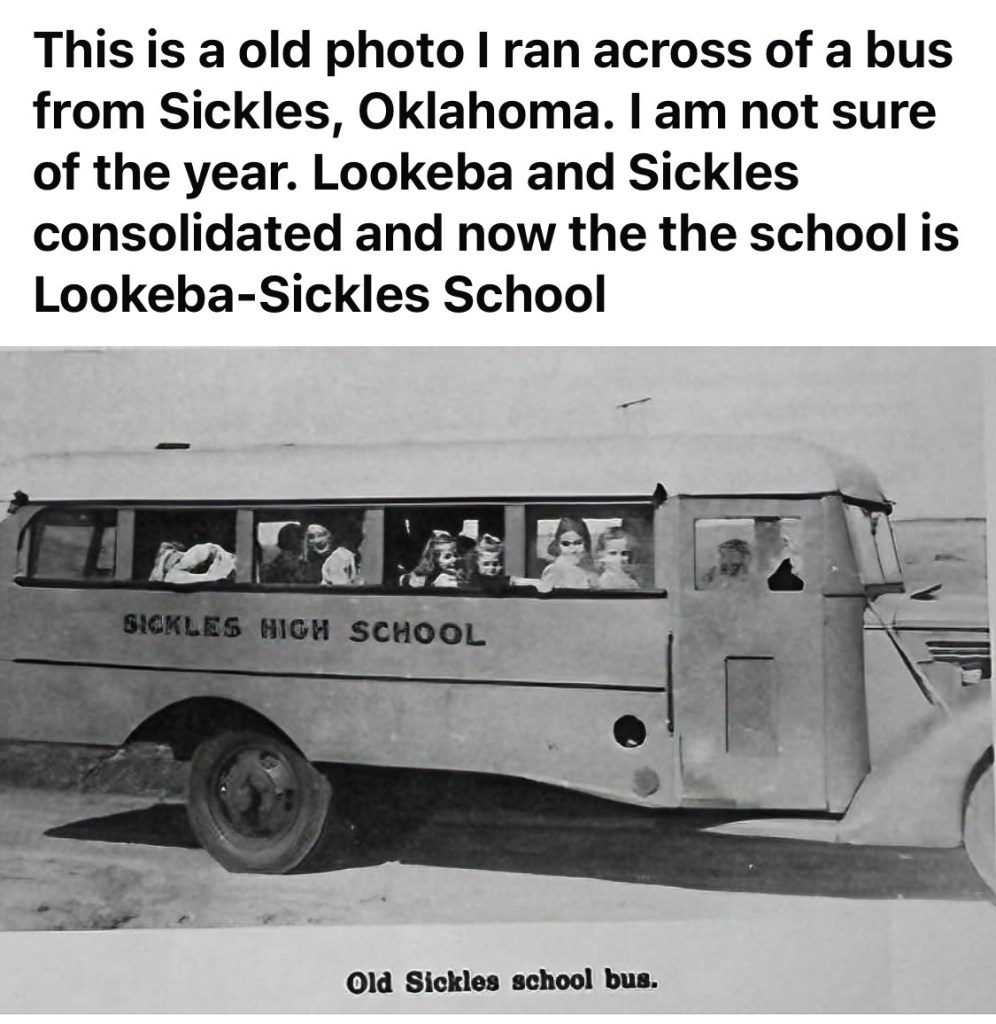

Just down the way sat Sickles. It was often written as “Sickless” in old letters and memories. The name came from Hiram Sickles, a farmer. His influence stretched further than the little community ever did on a map. Sickles was more minor—more crossroads than village. Yet, it had what every reasonable Oklahoma settlement needed. This included a school, a store, and neighbors who shared tools and gossip. They also offered weather predictions no weather forecaster can match.

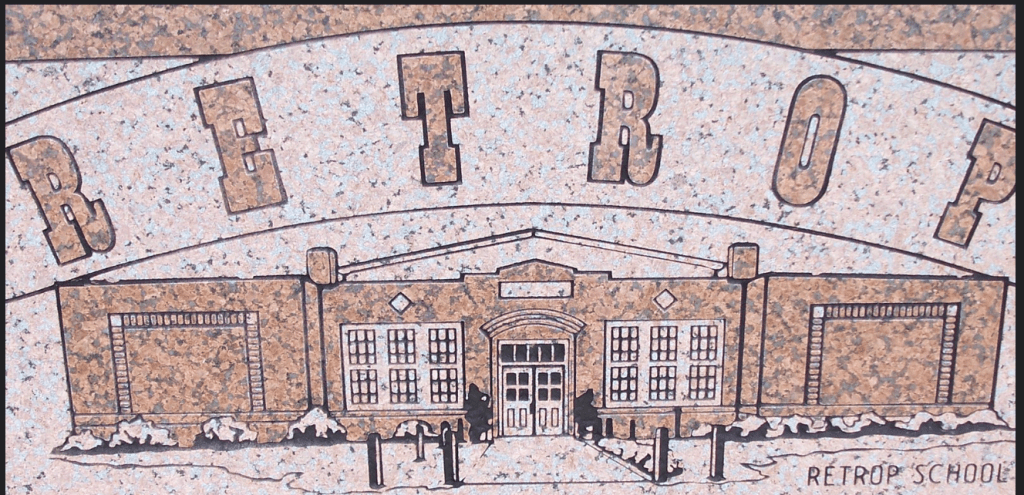

For decades, the two towns lived like siblings. Lookeba was the older and slightly larger child with a stronger sense of identity. Sickles was the quieter shadow tucked between wheat fields and pastures. Students from both communities would merge into the Lookeba-Sickles School District. They formed friendships and rivalries. These bonds outlasted the buildings that once separated them. Generations of ballplayers, farm kids, and rodeo hopefuls came together under one mascot. They were often unaware of the deep connections spanning miles of family history. This history converged whenever the gymnasium lights buzzed to life for Friday night basketball.

Time, as it always does in rural Oklahoma, thinned the businesses and emptied the old stores. The Sickles school population lowered long before its name faded from county conversations. Lookeba’s Main Street slowed to a pace that matched the prairie winds. But something remained—something that belongs only to towns like these.

A sense that history is not made by headlines but created by the people who refuse to disappear. Families make history. Their names still ring out in church directories, land deeds, and the memories of class reunions.

Stand in Lookeba today at dusk. The sun lays gold across the wheat. The cicadas start their evening hymns. You can still feel them: Lowe. Kelly. Baker. Sickles. The founders, the farmers, the families whose footprints shaped the land long before highway maps tried to catch up.

Somewhere between Lookeba and where Sickles still stands, you hear echoes of school bells if the wind is right. You also hear screen doors slamming. You hear the voices of children running toward a future. A future no one knew. But, it was a future built on names still remembered.

Lookeba-Sickles High School is where I graduated many years ago. And, I still remember walking down the hallway and out the doors the last day of school. The thought of entering adulthood was on my mind. As I got to my car, I made a once glance back. A final goodbye, and I was gone.

By Benjamin GroffMedia© | benandsteve.com | ©2026