A Story By: Benjamin Groff© Groff Media 2024© Truth Endures

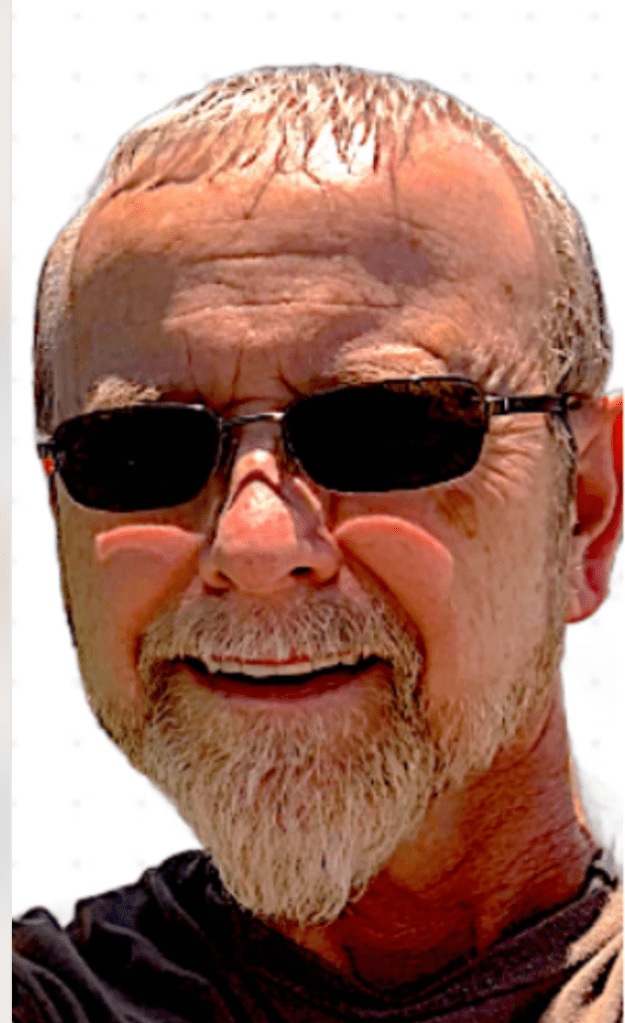

At 85, Elmer had circled the globe twice, a testament to his adventurous spirit. He was known as a reliable friend to his neighbors, colleagues, and family, earning their trust and respect. His life was a rich tapestry of experiences woven from the people he met and the challenges he overcame.

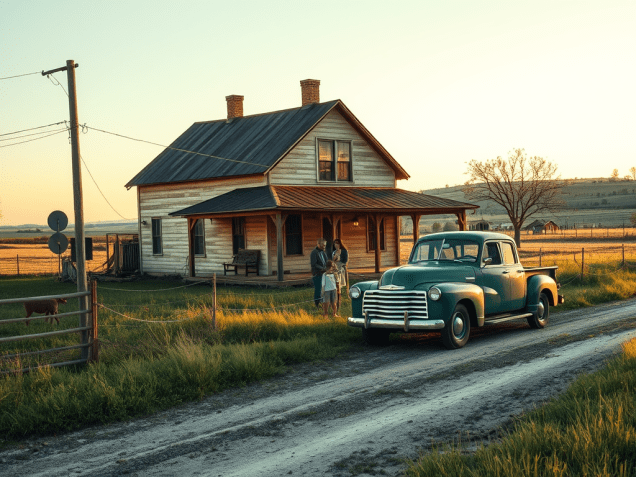

No one knew that since 80, Elmer had been slowly forgetting things. Elmer lived alone, having never had children. The love of his life, Bill, had been his husband. Together, they built a home and a life they had fought for since the 1960s. But Bill had died in the 1990s of AIDS, leaving Elmer to quietly close himself off from the world, no longer inviting people into his home.

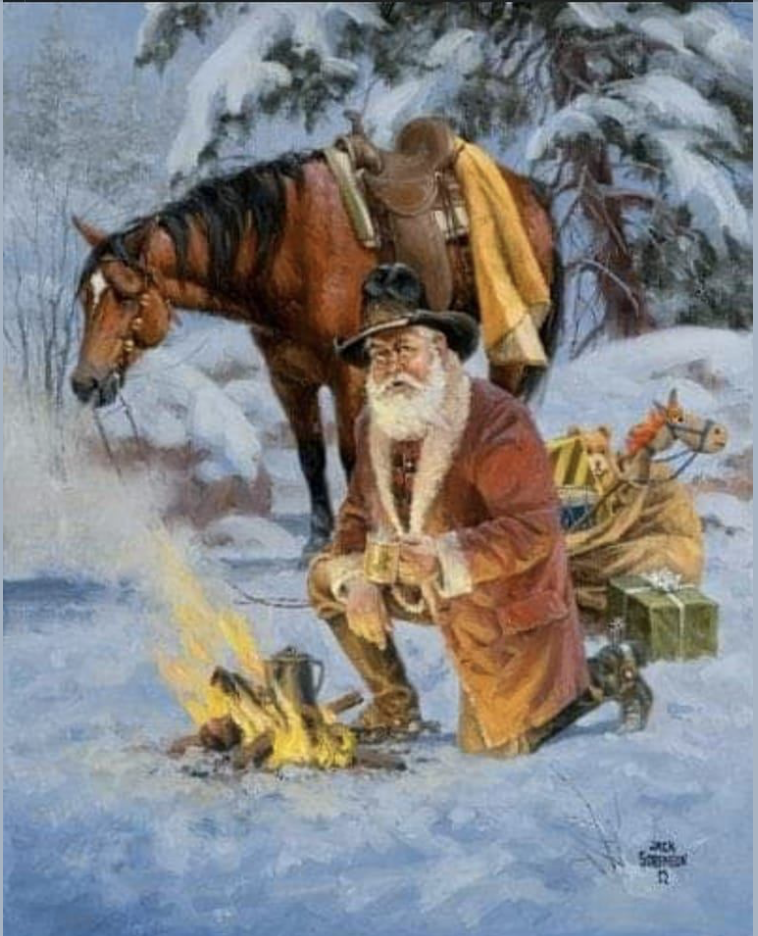

In the last five years, Elmer had taken to raising quarter horses, finding solace in their company. But as time passed, he needed help to keep up with them. Elmer would leave gates open and have to chase the horses down or forget to feed them on time. Once, after a late ride, he left a horse saddled overnight. The guilt he felt was overwhelming, and he knew something was wrong.

A visit to the doctor revealed a possible explanation: lack of sleep and depression, likely linked to his grief over Bill’s passing.

Determined to regain control, Elmer began taking medication to lift his spirits and help him sleep. He convinced himself he could manage. On Wednesday, Elmer had an appointment with a buyer interested in purchasing two of his horses. He thought selling them might relieve some of the pressure, leaving him with only one horse to tend to.

But Elmer had other concerns. He now shared his home with a group of stray cats that seemed to have appeared out of nowhere, along with his faithful companion, Roger, a golden-eyed Saint Bernard. Roger was more than just a pet; he was Elmer’s protector, especially when the owner began drinking whiskey.

Elmer tried to manage his responsibilities—his horses, cats, dog, and the home he had shared with Bill—but his mind kept slipping. He believed that Bill might still come home, even calling Bill’s sister, Matilda, to ask if she’d seen him. Matilda gently reminded him that Bill had passed away years ago.

Realizing he had let his secret slip, Elmer quickly covered by asking if she had seen a particular picture of Bill.

Matilda, sensing something was wrong, insisted on visiting.

“Elmer, damn it, I need to see you. I haven’t been over in two years, and it’s time we have dinner!”

Matilda demanded.

Caught off guard, Elmer couldn’t refuse.

“In the morning would be fine,”

He replied, resigned to the visit.

After hanging up, Elmer sorted through his mail and found a late notice from the electric company. He had forgotten to pay his bill, and the power got scheduled to be disconnected the next day. Frustrated, Elmer called the company, only to learn he had missed several payments. He assured them he would take care of it first thing in the morning.

Elmer hung up the phone, the weight of the day pressing down on him. His forgetfulness had become more frequent and more troubling. Once, he ended up in a faraway town, wondering how he got there. He had forgotten the names of his horses, even his dog Roger, and once needed help figuring out what his car keys were for.

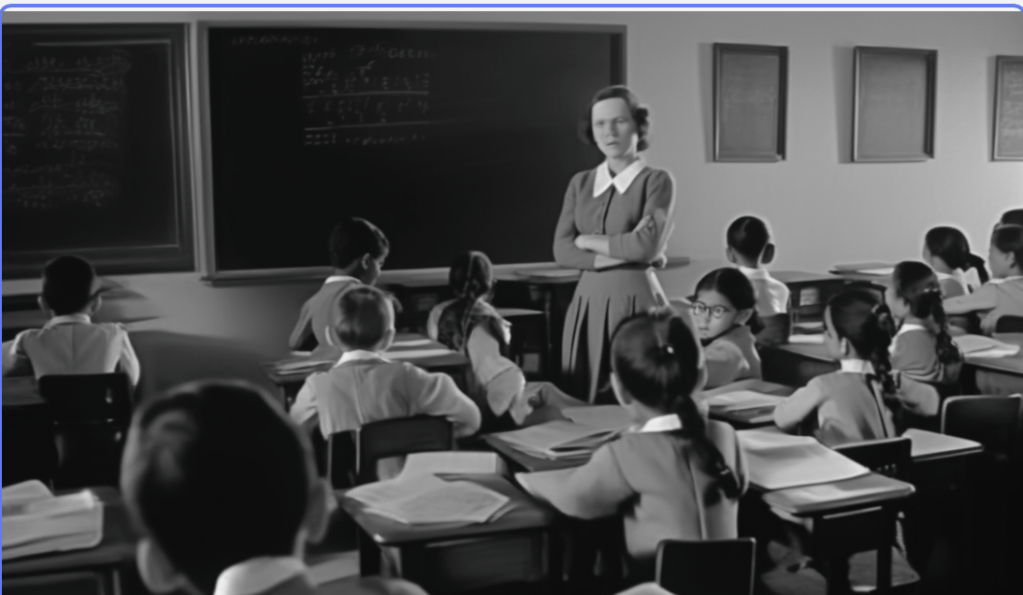

That evening, Elmer and Roger settled into the family room to watch a news program, a series on Alzheimer’s. The more Elmer watched, the more convinced he became that he was suffering from the disease. The thought terrified him. He looked at Roger and grumbled,

“I’ll be damned if I’m going out like that! I’m going out on top, not lingering around aloof and half-quacking!”

Determined to end his life on his terms, Elmer went to the liquor cabinet, packed five large bottles of whiskey into a box, grabbed some water, and called for Roger to get into the truck. He was visiting their favorite spot to watch the sunset—his and Bill’s particular spot. There, he planned to drink himself into oblivion and end his life.

As they arrived at the overlook, Elmer realized with a bitter laugh that he had forgotten the gun he intended to use.

“Shit! I forgot the gun to shoot myself with!”

He muttered. Searching for an alternative, he looked for a rope to hang himself, but that too was missing.

“Well, shit, Roger! I don’t have a rope.”

Roger, ever loyal, had been trained by a local bartender to remove the keys from Elmer’s truck whenever the pet’s master started drinking heavily. As Elmer continued drinking, Roger did just that, hiding the keys.

Now thoroughly drunk, Elmer looked at Roger and slurred,

“What the hell did we come out here for?”

He was confused, unable to remember his grim plan. By

2:00 AM, the sky was pitch dark, and both man and dog were asleep in the truck.

Back at Elmer’s home, the morning brought concern.

Matilda arrived, along with the horse buyer and the electric company. But Elmer was nowhere to be found. Sensing something was wrong, Matilda called out to the others,

“Elmer would never allow a cat inside his house; something is wrong here!”

The electric company worker radioed his office to report a possible missing person, while Matilda assured them she would cover the bill to keep the power on. Their primary concern was finding Elmer.

The horse buyer suggested,

“I figure Elmer’s out at the overlook like he is every year at this time. He and Bill went there every year on the 15th of this month for their anniversary.”

Meanwhile, Elmer was waking up at the overlook, groggy and disoriented. Roger, ever the guardian, brought him the truck keys.

Elmer looked at the dog,

“Roger, ‘ole boy, why in the hell are we out here? And who brought all these damn whiskey bottles?”

With no recollection of his plan, Elmer drove home, where a flurry of activity awaited him.

As he approached the gathering, he overheard someone say,

“A homeowner has gone missing, and everyone’s looking for him.”

Elmer, confused, asked, “Why are they doing it here?”

“They think this is where it happened,” came the reply.

“They think he went missing here?

I was here until 10 PM last night and didn’t see anything,” Elmer responded.

The man shouted to the Sheriff, “This man says he was here until 10 PM last night and didn’t see anything!”

The Sheriff called back, “What’s his name?”

Elmer, finally realizing the situation, shouted,

“ELMER!”

You’re on my damn land, damn it!”

Matilda reached Elmer, talked to him, and promised he would never be alone. She would ensure he did not get treated like others he had witnessed on television.

Matilda said,

“Elmer, you are 85. Other parts of you are more likely to take you out before the mind takes you!”

Elmer, looking around, remarked,

Matilda, you have a way of comforting the soul. Are you the one who brought all these damn cats out here and turned them loose in my house?

Matilda asked Elmer where he had been and what he had been doing.

Elmer said,

Truthfully, I don’t know. Roger and I just woke up at the overlook, and it was yesterday, today, and the 15th all coming together. I didn’t realize it.

Matilda confronted Elmer, saying, “Well, Roger had more to say about. In fact, a lot more. You see, he gave me this note you gave him. It is a goodbye note you put on his collar last night.”

Elmer’s face brightens as if a light bulb had gone on, responds,

Now I remember what I went out there for, but I just remembered that I need to bring—ugh, ice.

Matilda snaps back

Nice try, old man. I know what you are thinking, and it can’t happen. You still have a reason. And you can’t die until you no longer have a reason, like it or not. Your reason is not up yet! So get used to it. You still have a Reason

For more information on Alzheimers and Dementia Illnesses visit https://www.alz.org Also check when you can participate in the walk to prevent Alzheimers 2024!