The Year Many Were Born And The World That Shaped It

By Benjamin GroffMedia© | benandsteve.com | ©2026

A topic came up recently about naming the most interesting—or most defining—events from the year you were born. For me, that year was 1963, which was sixty-two years ago. It was a year that carried an unusual weight, filled with moments of deep loss alongside remarkable progress and hope.

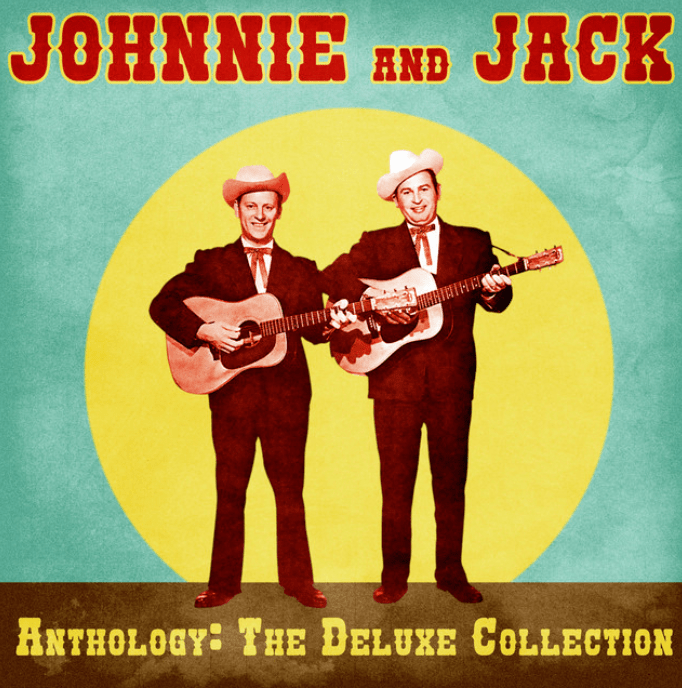

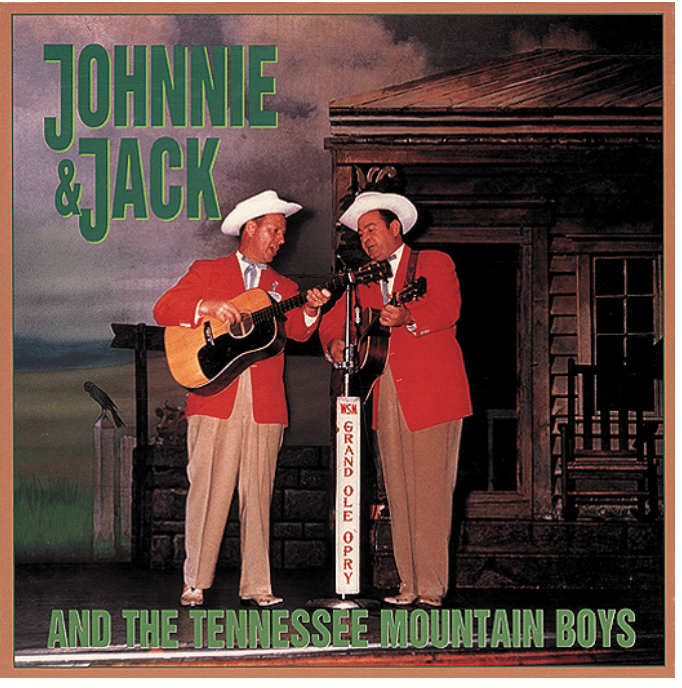

For fans of country music, 1963 was especially heartbreaking. In March, a plane crash claimed the lives of Patsy Cline, Hawkshaw Hawkins, Cowboy Copas, and Cline’s manager. Just a few months later, another aviation accident occurred. It took the life of Jim Reeves, one of the genre’s most beloved voices. The sorrow didn’t end there. Jack Anglin, one half of the duo Johnny & Jack, was killed in a car accident. He was driving to attend Patsy Cline’s memorial service. In a matter of months, country music lost several of its brightest stars, leaving a lasting scar on the industry.

Nationally, the year is most remembered for tragedy. President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, an event that stunned the nation and the world. Two days later, the man accused of the assassination, Lee Harvey Oswald, was himself shot and killed. Oswald’s murder caught on live television by the shooter Jack Ruby, a Dallas nightclub owner. Because both men died before standing trial, no jury verdict was ever rendered regarding the assassination itself. While the Warren Commission later concluded that Oswald and Ruby acted alone, lingering questions have remained for decades.

There has also been confusion surrounding Jack Ruby’s legal fate. Ruby was convicted of murder with malice in March 1964 and sentenced to death, but that conviction did not stand. In October 1966, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals overturned the verdict. The decision was due to excessive pretrial publicity. The court ordered a new trial. Before that retrial could occur, Ruby died on January 3, 1967, from complications related to lung cancer. As a result, no final conviction was in place at the time of his death.

Yet 1963 was not defined by tragedy alone.

Despite its losses, the year was also marked by hope, courage, and meaningful progress. On August 28, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech during the March on Washington. The speech inspired millions. It accelerated the push toward civil rights legislation that would soon follow. In science, Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space, orbiting Earth aboard Vostok 6—a milestone celebrated around the globe.

Popular culture flourished as well. The Beatles rose to international fame, bringing a sense of excitement and unity to a generation. Television, animation, and film offered families shared moments of comfort during a rapidly changing time. On the world stage, the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom signed the treaty. This treaty was the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. This treaty represented a hopeful step toward easing Cold War tensions.

Looking back, 1963 stands as a year of contrast—one of profound sorrow and extraordinary progress. It reminds us that even in times of loss, history continues to progress. Resilience and creativity shape it. There is also the enduring hope for something better.

By Benjamin GroffMedia© | benandsteve.com | ©2026