A True Story By: Benjamin Groff© Groff Media 2024© Truth Endures

Join Us For a Coffee Break!

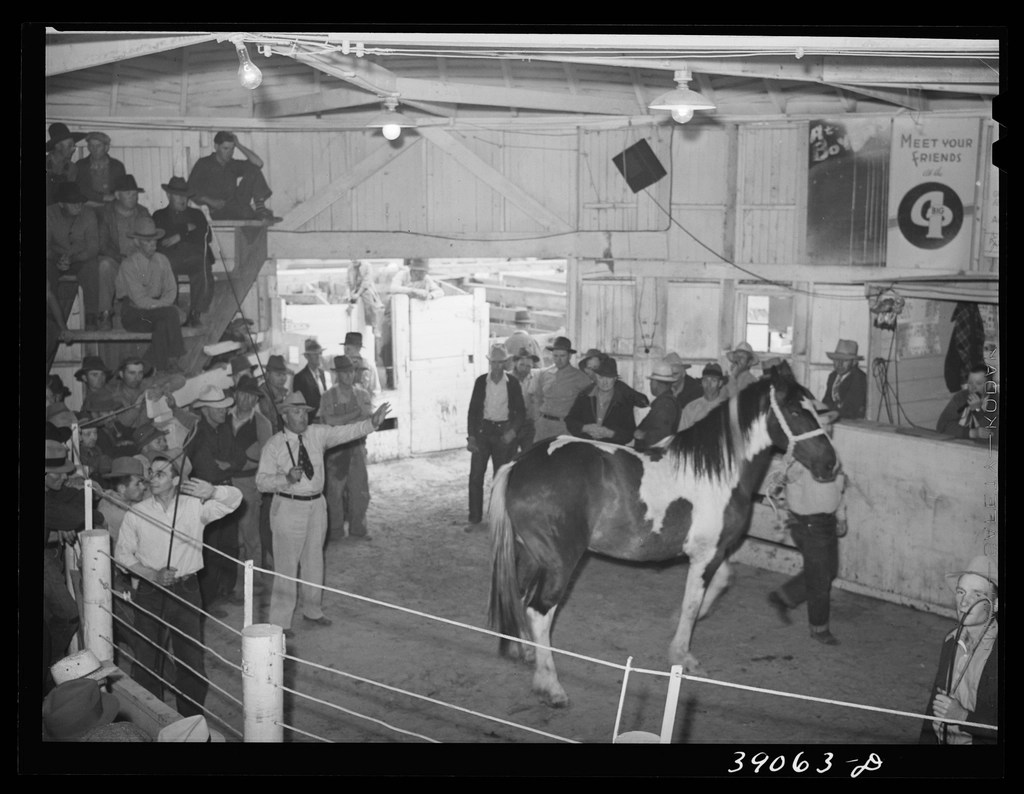

If you’ve read previous stories about my dad and me heading to horse sales during my youth, you’ll know it was a ritual we performed every Friday and Saturday night. It wasn’t just about the horses but the time we spent together and the bond we shared. Somewhere, someplace, we could always find a horse sale. And if the horse sales took a break in the summer, we’d catch a rodeo, no matter how far we had to drive.

I saw more of Oklahoma at night than I ever did during the day. That’s when my dad and I would drive the state highways, venturing wherever the road took us. But this particular trip was different. We were going to our regular sale in the city, about 30 miles from home.

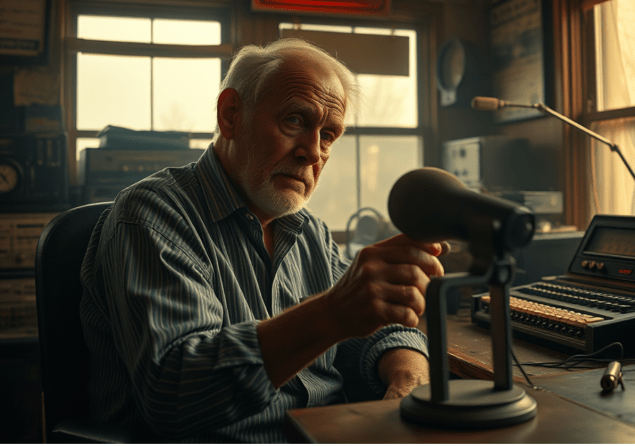

It was the 1970s, and Citizen Band (CB) radio had become all the rage. I had three older brothers, all grown, who installed CB radios in their vehicles, catching my dad’s attention. Before long, we also had one in our pickup, tuned in, and received signals from all over. Dad outfitted our rig with twin whip antennas and a power mic; he even considered adding an amplifier but decided against it after hearing the FCC might crack down on him. My dad always did things by the book. So we were content rolling down the highway, our handles “Big Jake” for him and “Gentle Ben” for me.

We’d pick up reports about ‘Bears in the Air’ and ‘Bear Setups’ just down the road. Although we were doing the speed limit, Dad would ease up on the accelerator to humor me, making me think those reports were helping. On our way to the horse sale that night, we heard a spectrum of new voices on the air—voices we’d never heard before.

I told my dad they were coming in too consistently and clearly to be skip signals; they had to be close.

He said, “Let’s listen to them a minute.”

As we tuned in, these voices discussed being in Indian City and staying set up all night. They invited anyone to come by, mentioning they were at the Coffee Break on the east side of town, near the rodeo grounds. The ‘Coffee Break’ was a popular gathering spot for CB radio enthusiasts to meet, socialize, and share their experiences.

Indian City was the nickname for Anadarko, where we were headed for the horse sale. The town was known for its tourist attraction, Indian City, USA, with teepees and all—a gimmick that drew in visitors.

Dad keyed up the mic and gave a breaker. One of the new voices responded. Dad explained we were headed to a horse sale and might drop by for a cup if the horses weren’t any good later.

They said,

“Come on by! Have you ever been to one of our Coffee Breaks?”

Dad replied,

“That’s a big negatory!”

Well then,” they said,

“park wherever you can and find Booth 12—that’s where we’re set up.“

We went to the horse sale, and I spied a horse or two I thought Dad might be interested in. But around 11:00 PM, he nudged me and said,

“Let’s go to the Coffee Break. I want to see what it’s about, and I’m sure you do, too.”

I wanted to say yes, but those two horses had not come up. We had a herd of horses back home, so missing one or two wouldn’t matter. Besides, I was curious about what we’d get into at this place.

When we arrived at the rodeo grounds, the area was full of campers, RVs, and tents—huge tents, at least to me. The tent poles seemed massive, with lighting strung throughout by wire. I wasn’t sure if it was safe, but I trusted my dad as he led the way.

We found what we thought was Booth 12, where a lady sat in a folding lawn chair. She looked up at me and said,

“Hi, sweetie. You run away from home?”

I quickly replied,

“Oh no, I’m here with my dad; we’re looking for Booth 12.”

She smiled, a crooked grin on her face, and said,

“You’re looking for Honey Badger! HONEY BADGER, GET YOUR ASS OUT HERE!”

From around the corner came a short man with a balding head and a potbelly. He hadn’t shaved in a week and said,

“What is it, Wilda? You don’t have to yell! Oh, hello.”

I whispered to my dad,

“The lady’s name is Wilda,”

Mimicking the style of Sgt—Friday and Officer Bill Gannon on Dragnet.

My dad looked down at me and used his favorite phrase when I tried to do impressions:

“Don’t be stupid.”

Honey Badger had sharp ears because when he heard Dad’s voice, he said,

“I know him—that’s Big Jake. We talked to you a few hours ago, and I’ve heard you before when we passed through these parts. I’m Honey Badger. Let me show you around. Wilda, you want to watch the boy?”

Dad told me to stay with Wilda, promising he’d be right back. I wasn’t sure what was happening, but I decided to start searching if I didn’t hear from him by the top of the hour. For all I knew, these could be aliens from another planet up to something strange. I had just turned ten, and the year before, my dad and I had to walk home after the truck we test-drove broke down on our way home from a horse sale. I could take on whatever might be behind those dark tents—or at least that’s what I told myself.

In the meantime, Wilda and I managed to strike up a friendship. She told me they were from Kansas and had retired. Honey Badger worked with honeybees as a hobby, hence his CB name. She said,

“And I’m the Queen Bee; I get on that radio and just Buzz.”

Wilda looked like a much older Ms. Kitty—a short, broad, ancient Ms. Kitty. Her voice reminded me of one of the blonde girls on The Andy Griffith Show who gave Andy and Barney a hard time. She was a sweet soul who must’ve lived quite a life. She got me a hot cup of Pepsi and talked about missing her TV show to come on this trip with Honey Badger. But she said, –––

“It’s worth it. You don’t know when one of you is going to die. You want to do all the things in life you can before you call it quits.”

She shared stories about her and her husband’s adventures, and I did my best to look interested, though I only sometimes followed along.

Dad must have been gone for thirty minutes. I had no idea what he was doing, but I sure had a lot of intelligence gathered from Queen Bee to share with him.

When he finally returned, he scooped me up, thanked Queen Bee for having us over, and assured her we’d made friends on the southern plains that stretched far north.

As we got into the pickup and headed home, I noticed Dad pushed his hat back on his head, just like he did at Christmas when he and one of my uncles secretly toasted shots at my grandparents. He was in such a good mood, so I shared my findings. –––

“So,” I began, “Wilda—or Queen Bee—said they’ve been to several states doing Coffee Breaks because she can’t have kids, and he doesn’t want any. He also has some car problems that he can’t fix. She told me he lost his left nut in the war. But I don’t think he’s still driving the same car he had when he was in the war.”

At the time, I thought whatever Dad had been up to must’ve been a lot of fun because he laughed all the way home. Within a year or two, I realized Honey Badger hadn’t lost a lugnut at all—but maybe it was better when he had.

There are Memorials left behind for those CB Radioer’s who’ve met up and passed on by clicking here.